New paragraph

NEW ARTICLES

The Times' journalist Andrew Ellson's critique of government's LTN review

posted on X

26 March 2024

NOTES on Research Report

Generally speaking, the guidance to councils appears quite sensible and is clearly intended as a rebuke to local authorities that have chosen to implement LTNs without proper consultation or support from local residents. Yet, in recent days many LTN advocates have suggested that the guidance is some sort of vindication, saying it only reinforces what councils have been doing already.

That is very far from the truth. For example, the guidance states that councils “should use objective methods, such as professional polling to British Polling Council standards, to establish a truly representative picture of local views”.

This is quite a stringent requirement and should, in theory, mean local authorities can no longer get away with consultations (designed by cycling lobby groups) that contain leading questions and can easily be gamed by activists on either side of the debate.

The guidance also reminds councils that they

should consult bus operators in advance of implementing an LTN, something we know some authorities, such as Lambeth, have not been doing. They are also told to consult the emergency services – something you might not think they would need reminding about but the LTN review reports that 16 per cent of schemes were implemented without talking to the police, fire, or ambulance services.

Another example from the guidance where councils are going to have to up their game comes in the section called “design principles for effective LTNs”. This states that schemes “should have clear aims and objectives, with a rationale and evidence to support intervention and measurable metrics of success”.

This is going to present a challenge to many councils which, up to now, have chosen not to identify specific aims and objectives or defined metrics of success. Holding councils to this higher standard can only be welcome.

However, the “measurable metrics of success” are only as good as the data that the councils present and sadly the

vehicle counting tubes that most authorities use can hugely under-report traffic levels, particularly on congested boundary roads.

The data these tubes provide can also be gamed by where and when they are placed. It is therefore disappointing that the guidance does not also require councils to conduct some form of supplementary human counting of traffic on the most congested roads to validate the data provided by tubes.

The guidance, rightly, also has plenty to say about what councils must do

to ensure schemes do not make life worse for the disabled. Sadly, we know this is necessary because the review states that more than one in ten LTNs were implemented without disabled groups even being consulted, which seems an abject failure of government. The guidance reminds councils that “accessibility requirements and the Public Sector Equality Duty apply to all measures”. It adds that councils “should always consider exemptions for Blue Badge holders”, which we know in many cases has not been happening and is something many LTN advocates object to for some unfathomable reason.

The guidance also states that councils should consider giving local residents and those making deliveries permits to travel through restrictions. Again, this seems like a sensible idea that would result in the schemes only hitting genuine “through traffic” and having much greater public support but is an anathema to most LTN advocates. However, because the guidance states only that councils should consider this then the chances of many actually doing it are slim to none.

Another area where councils are going to have to up their game is on planning and monitoring LTNs. The guidance says councils should collect “appropriate data” in advance and during monitoring to ensure there is “a robust evidence base on which to develop proposals and make decisions”. We know that in many LTNs this simply has not happened. My local LTN, for example, was introduced in 2020 despite the last traffic count on the main boundary having been conducted in 2014.

The guidance goes on to list the data councils are expected to gather and this is going to make it much harder for councils to justify new LTNs and keep them once introduced. It says the data should include “traffic counts, pedestrian and cyclist counts, traffic speed, journey times both within and around the perimeter, patterns of traffic flow, air quality data (particularly the possible air quality impacts of displaced traffic), public opinion surveys and consultation responses”.

The guidance to monitor journey times around the perimeter of LTNs before and after implementation is particularly welcome and I cannot think of a single case where this has been done so far (although I am prepared to be corrected on that). There are also other parts of the guidance that, if adopted by councils, will significantly change the design of future schemes. For example, the guidance notes that physical barriers “are more likely to be appropriate for small schemes only”. This has not been the case up to now.

The guidance also states that

“warning notices should be issued for first-time contraventions for a period of 6 months after new schemes are implemented, or existing ones are made subject to camera enforcement for the first time”. This has not been happening at present. It adds that “traffic management schemes should be designed to work for local communities and never as a revenue raising tool”. Ha, Ha!

All of this seems eminently sensible but is only as good as councils’ willingness to adhere to the guidance and the consequences for them should they choose to ignore it. Sadly, there is little substance in the guidance on how it will be enforced. It only really states that the transport secretary “reserves the right to take into account adherence to this guidance in relevant future transport funding allocations”. That is not a very big stick. There is also a commitment to consult on removing access to DVLA records for recalcitrant councils, but this looks fraught with difficulty and, realistically, will likely never happen.

This is the main flaw in the guidance – there is little that can be done if councils choose to ignore these protocols. There is not even a mechanism by which disgruntled residents or groups can submit evidence to the DfT of a council’s failure to adhere to the guidance. Basically, this guidance relies on the good will of councils and those in charge of local transport policy being sensible, moderate, and rational. Many who have engaged with councils over LTNs know this is all-too often not the case. And that is a shame because otherwise this guidance is generally good and would lead to better policy if it was adhered to.

In many ways it is astonishing that councils should need reminding of so many simple principles of good governance but sadly too many LTNs have been implemented without consideration of the impacts beyond the area itself while residents who identified problems and shortcomings or suggest sensible mitigations have, in many cases, not just been ignored but cast as reactionaries or petrol heads.

Let’s hope this guidance changes things but I am not hugely optimistic.

NOTES on Research Report

Generally speaking, the guidance to councils appears quite sensible and is clearly intended as a rebuke to local authorities that have chosen to implement LTNs without proper consultation or support from local residents. Yet, in recent days many LTN advocates have suggested that the guidance is some sort of vindication, saying it only reinforces what councils have been doing already.

That is very far from the truth. For example, the guidance states that councils “should use objective methods, such as professional polling to British Polling Council standards, to establish a truly representative picture of local views”.

This is quite a stringent requirement and should, in theory, mean local authorities can no longer get away with consultations (designed by cycling lobby groups) that contain leading questions and can easily be gamed by activists on either side of the debate.

The guidance also reminds councils that they

should consult bus operators in advance of implementing an LTN, something we know some authorities, such as Lambeth, have not been doing. They are also told to consult the emergency services – something you might not think they would need reminding about but the LTN review reports that 16 per cent of schemes were implemented without talking to the police, fire, or ambulance services.

Another example from the guidance where councils are going to have to up their game comes in the section called “design principles for effective LTNs”. This states that schemes “should have clear aims and objectives, with a rationale and evidence to support intervention and measurable metrics of success”.

This is going to present a challenge to many councils which, up to now, have chosen not to identify specific aims and objectives or defined metrics of success. Holding councils to this higher standard can only be welcome.

However, the “measurable metrics of success” are only as good as the data that the councils present and sadly the

vehicle counting tubes that most authorities use can hugely under-report traffic levels, particularly on congested boundary roads.

The data these tubes provide can also be gamed by where and when they are placed. It is therefore disappointing that the guidance does not also require councils to conduct some form of supplementary human counting of traffic on the most congested roads to validate the data provided by tubes.

The guidance, rightly, also has plenty to say about what councils must do

to ensure schemes do not make life worse for the disabled. Sadly, we know this is necessary because the review states that more than one in ten LTNs were implemented without disabled groups even being consulted, which seems an abject failure of government. The guidance reminds councils that “accessibility requirements and the Public Sector Equality Duty apply to all measures”. It adds that councils “should always consider exemptions for Blue Badge holders”, which we know in many cases has not been happening and is something many LTN advocates object to for some unfathomable reason.

The guidance also states that councils should consider giving local residents and those making deliveries permits to travel through restrictions. Again, this seems like a sensible idea that would result in the schemes only hitting genuine “through traffic” and having much greater public support but is an anathema to most LTN advocates. However, because the guidance states only that councils should consider this then the chances of many actually doing it are slim to none.

Another area where councils are going to have to up their game is on planning and monitoring LTNs. The guidance says councils should collect “appropriate data” in advance and during monitoring to ensure there is “a robust evidence base on which to develop proposals and make decisions”. We know that in many LTNs this simply has not happened. My local LTN, for example, was introduced in 2020 despite the last traffic count on the main boundary having been conducted in 2014.

The guidance goes on to list the data councils are expected to gather and this is going to make it much harder for councils to justify new LTNs and keep them once introduced. It says the data should include “traffic counts, pedestrian and cyclist counts, traffic speed, journey times both within and around the perimeter, patterns of traffic flow, air quality data (particularly the possible air quality impacts of displaced traffic), public opinion surveys and consultation responses”.

The guidance to monitor journey times around the perimeter of LTNs before and after implementation is particularly welcome and I cannot think of a single case where this has been done so far (although I am prepared to be corrected on that). There are also other parts of the guidance that, if adopted by councils, will significantly change the design of future schemes. For example, the guidance notes that physical barriers “are more likely to be appropriate for small schemes only”. This has not been the case up to now.

The guidance also states that

“warning notices should be issued for first-time contraventions for a period of 6 months after new schemes are implemented, or existing ones are made subject to camera enforcement for the first time”. This has not been happening at present. It adds that “traffic management schemes should be designed to work for local communities and never as a revenue raising tool”. Ha, Ha!

All of this seems eminently sensible but is only as good as councils’ willingness to adhere to the guidance and the consequences for them should they choose to ignore it. Sadly, there is little substance in the guidance on how it will be enforced. It only really states that the transport secretary “reserves the right to take into account adherence to this guidance in relevant future transport funding allocations”. That is not a very big stick. There is also a commitment to consult on removing access to DVLA records for recalcitrant councils, but this looks fraught with difficulty and, realistically, will likely never happen.

This is the main flaw in the guidance – there is little that can be done if councils choose to ignore these protocols. There is not even a mechanism by which disgruntled residents or groups can submit evidence to the DfT of a council’s failure to adhere to the guidance. Basically, this guidance relies on the good will of councils and those in charge of local transport policy being sensible, moderate, and rational. Many who have engaged with councils over LTNs know this is all-too often not the case. And that is a shame because otherwise this guidance is generally good and would lead to better policy if it was adhered to.

In many ways it is astonishing that councils should need reminding of so many simple principles of good governance but sadly too many LTNs have been implemented without consideration of the impacts beyond the area itself while residents who identified problems and shortcomings or suggest sensible mitigations have, in many cases, not just been ignored but cast as reactionaries or petrol heads.

Let’s hope this guidance changes things but I am not hugely optimistic.

IN THE NEWS

Low-traffic zones ‘just greenwashing’, says lobby group

Monday May 22 2023, 12.01am, The Times

Low-traffic neighbourhoods might result in more miles being driven

JOHNNY ARMSTEAD/ALAMY

The government has been accused of “greenwashing” a key part of its active travel policy after the Department for Transport said it could give no evidence that low-traffic neighbourhoods reduced the number of miles driven.

An official responsible for the schemes, known as LTNs, which ministers present as environmentally friendly, said no studies on the effect on distance travelled had been requested because “LTNs don’t exist to reduce miles driven”.

The statement has alarmed campaigners who query LTNs’ effect on the climate. Clair Battaglino, of Social and Environmental Justice, a group set up to lobby against LTNs, said: “Until we see better evidence, claims that LTNs are good for the planet are just greenwashing.”

Greenwashing is the practice of using marketing spin to persuade the public that a product or policy is environmentally friendly when it is not.

An LTN in Oxford. The government has commissioned the University of Westminster to carry out a review of the schemes

ALAMY

In 2020, when hundreds of millions of pounds’ funding was announced for LTNs and other schemes to encourage cycling and walking, the government said the cash would help Britain to “build back greener”.

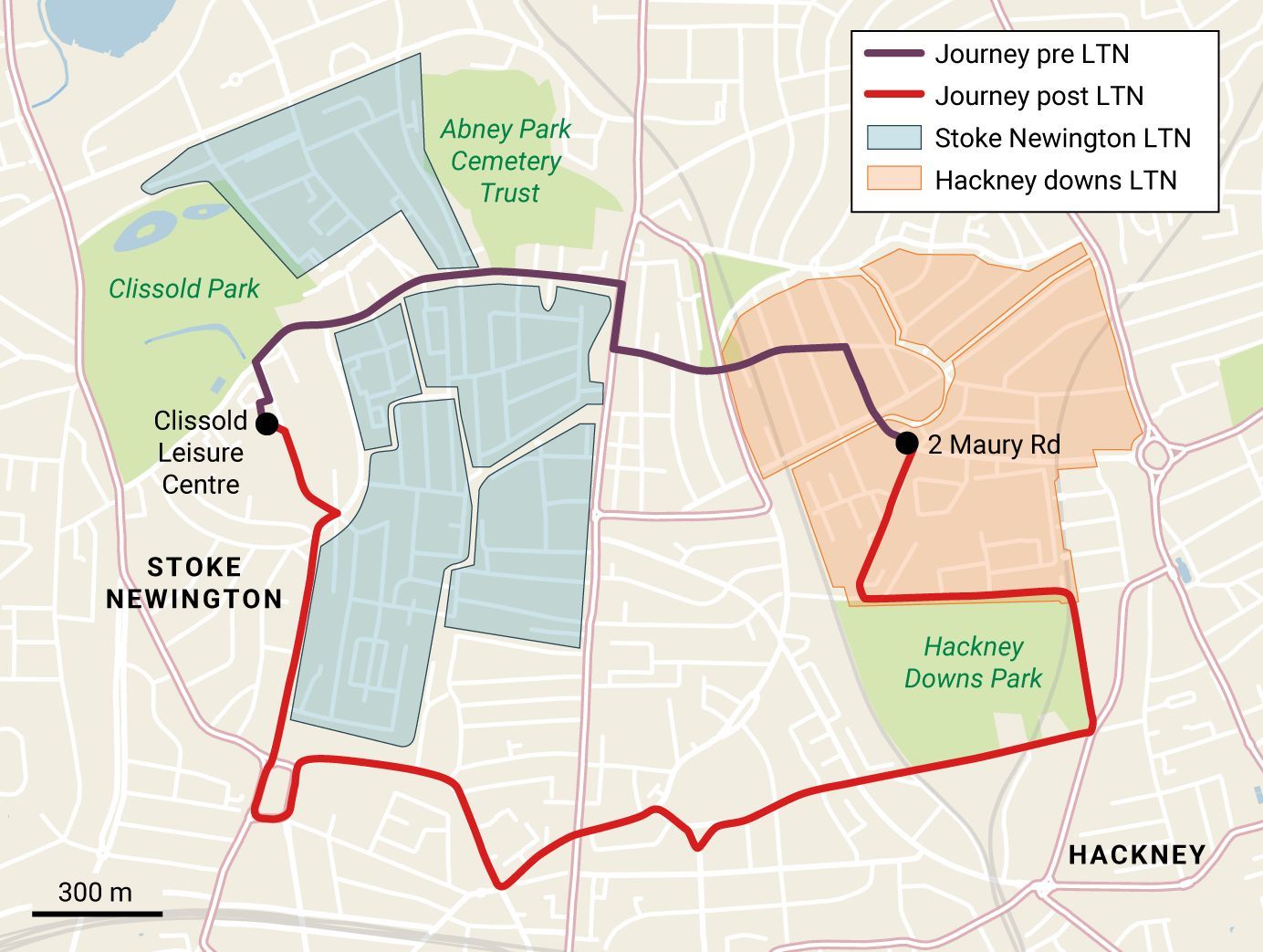

Since then LTN supporters have claimed that the schemes are a success by pointing to lower vehicle counts in and around some of the zones. Opponents say that even if a quarter of journeys are abandoned, which is far more than advocates claim can be expected, there could still be increases in distance driven because of the circuitous routes created for remaining traffic.

They say that if 40 vehicles an hour drove in an area before LTN restrictions were imposed, and each travelled 1km via the shortest route, then 40km would be driven in total. If a quarter of those journeys were abandoned after the introduction of the LTN but the remaining three quarters of trips became 500m longer, then the total kilometres driven would be 45.

That outcome could allow LTN advocates to celebrate a 25 per cent cut in traffic even though the distance driven and emissions created had increased by 12.5 per cent. This does not take into account extra engine idling in more congested boundary roads.

Whether distance driven rises or falls depends on the proportion of journeys abandoned and the average length of the diversions created.

Living Streets and the London Cycling Campaign (LCC), two charities that lobby for LTNs, claim that councils can expect 15 per cent of traffic to disappear but if 15 per cent of journeys are abandoned the previous example shows that the remaining journeys would only need to be 177m longer for the total distance to increase. The area covered by some recent LTNs means that diversions can add more than 2km to some journeys.

The Times asked the Department for Transport to supply evidence that LTNs reduced distance driven but it could not provide any. Asked why it had commissioned no research on this, an official said: “LTNs aren’t about reducing mileage necessarily and it’s for councils to choose the measures that they need.”

They suggested that nitrogen dioxide counts in and around some LTNs showed that the schemes could cut pollution although opponents point out that such figures may be influenced by where the measurements are taken, the Ultra Low Emissions Zone in London and lower traffic since the pandemic.

The government said it had commissioned the University of Westminster to conduct an independent assessment of LTNs. The study will be led by Professor Rachel Aldred, who is a former LCC trustee.